Elverda Thiesfeld Lincoln - WWII - Women Also Served

Pearl Harbor

I was eighteen years old when Pearl Harbor was bombed. Most people, including myself, didn’t know where Pearl Harbor was located. I was in the living room of our home, listening to the radio, when I heard the news that day…December 7, 1941. I was shocked and angry. The following day, many young men, from all over the country, stormed the recruiting offices to join the military services.

It wasn’t too long after Pearl Harbor that Pa and I left our Minnesota home to go to Washington where he had a job as a carpenter. Ma and the rest of the family followed not long afterward.

When the war started in 1941 until 1943, life in our family was changed in many ways. Rationing was one of the changes that took place then. Gas, sugar, fats and some canned goods all were rationed. The war effort heightened everyone’s resourcefulness. Since there were so many children in our family we didn’t feel like rationing was a big deal. In fact, sometimes we had more of these items during the war than we did before or after. Each member of our family had their own ration book.

Many men and women joined the services. Evidence of this was the existence of a plain blue small flag hung in windows of families who had sent a daughter or son off to war. A blue star was positioned on this flag for each member that had responded to their patriotic call. Some were replaced with gold stars, representing a father or son who had been killed.

Price controls affected everyone’s lives, especially in grocery stores. This was down to prevent price gouging. There was an expiration date on rationing stamps to prevent hoarding. Most stores willingly complied.

Because of rationing, households were forced to use margarine due to the shortage of butter. It was white and looked like lard. Inside this bag was a large yellow pill that had to be broken and then kneaded into the white. When thoroughly mixed, it looked like butter, but was not as tasty. The reason for this chore was the farmer’s rebelled if the factory-made margarine made it look like butter and they feared the sales of real butter would hurt them financially. In a few years, the farmers quit complaining and now margarine is colored yellow and looks like real butter.

I also remember hearing and reading about labor shortages resulting from the military’s demand for men, that left women to become not only riveters, but welders, mechanics, crane operators, truck drivers, gas station attendants, and bus drivers. At the same time, women continued to cook, clean, shop and care for their families.

Children who could afford it used their allowances to buy defense stamps and war bonds. They also participated in scrap drives to collect aluminum foil, metal and worn out tires. These items were recycled into the war effort.

I remember gas rationing and heard that this was done to keep people home. Fuel at gas pumps was under severe curtailment. For some people this restriction was difficult, especially young people wanting to drive around on Saturday nights for entertainment. The government imposed a nationwide speed limit of 35 miles an hour. Some people turned to the black market to obtain scarce items which usually meant paying higher prices.

Due to the scarcity of some food products, “Victory Gardens” were planted in almost everyone’s back yard. This relieved some of the stress of going without. It was a very successful program.

On September 19, 1943, at the age of 20, I enlisted in the US Navy as a WAVE. The initials of WAVES stood for Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service. Each time I walked past the post office in Yakima, Washington, where I lived, a large sign (about three feet by four feet) had an Uncle Sam pictured on it with his finger pointed at me saying I WANT YOU. The sign was positioned on a sandwich board almost on the sidewalk. There was no doubt it could be seen by everyone. The more I walked around this sign the more I took the message to heart.

At this time I was working a few days here and a few days there at various jobs and couldn’t stand any of them: jobs like working in a fruit cannery cutting pears in half, a few days untangling twisted piles of clothes in a laundry, applying for a job as a waitress and never showing up for duty, and mostly being unemployed.

Off to New York

One day I entered the Navy Recruiting Office and was informed the Navy was looking for girls with secretarial training which I had in high school. I signed up, passed the physical with flying colors, and before I knew it, was on a troop train to Seattle to join nine other enlistees traveling to Hunter College in the Bronx, New York City. Years later this same place became the headquarters of the United Nations.

It took five days to cross the USA on a troop train. The train was crowded with GIs on the way to the East Coast to report to embarkation points to serve in the European theater. We girls didn’t have a seat assigned to us. We spent all our time standing in the hallway, looking out the window or trying to get comfortable in any way we could inside the lavatory area. This area was large enough that three of us took turns lying on the floor so we could get some sleep. None of us took advantage of any GI’s offer of a seat. They were a rowdy, flirty bunch and we were scared of them.

A Navy bus met us at the train station. We were a sleepy, exhausted, bedraggled lot. An hour’s ride through New York City brought us to our dormitories, which were converted apartment complexes located outside the main gate of the college.

Our day began at 4:30 in the morning and ended at 9:30 at night. Boot camp was hard work, but I didn’t mind. We learned how to march in formation, had classes, took tests to find out what categories we were qualified for, and various other duties as assigned. Boot camp lasted four weeks. When I was issued my uniform I felt great. I now was on equal par with all the other girls. Pay was $50 a month. My confidence soared.

Weather in September in New York was hot and humid. Girls passed out while marching in formation. We just walked over them and continued on. We had ten minutes to eat our meals and be back in formation.

One day my platoon was last to be served lunch. Ordinarily food was plentiful, but for some reason the main course ran out. In order to solve this dilemma, trays of meat left over from the night before were reheated and served. About an hour later, recruits were passing out one after another and some were suffering from severe stomach pains. We were herded back to our quarters to recuperate from our ailments. We were sick all night, but the next morning we were back on duty. we were diagnosed with ptomaine poisoning.

The afternoon of the last Saturday of boot camp, we were given permission to go downtown. We were an excited bunch of women, and spent an enjoyable time, visiting Rockefeller Center, Times Square, Empire State Building, St. Patricks Cathedral and the Little Church Around the Corner. We admired the Statue of Liberty from afar, trying not to get lost, and worrying about getting back on time. Of course, we all had to load up on souvenirs and postcards.

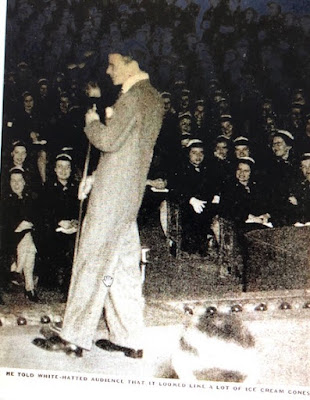

During that last week we were all herded into an auditorium to attend a musical performance put on by Frank Sinatra. He was so skinny that we couldn’t tell the difference between him and the microphone. Hours before this program we were given instructions to keep the noise level low-key. In fact, we were not allowed to remove our white gloves, no standing, no hollering, whistling or any other kind of loud exclamation. This performance was one of the first ones put on by Frank. Afterward, he disappeared through a back door, was escorted into a limousine by bodyguards, and we quietly returned to our barracks. Life Magazine published this event, so we knew it was a big deal.

When boot camp was over (one month later), I was sent to Cedar Falls, Iowa, for a three month crash course in advanced secretarial work which I really enjoyed. I took an aptitude test and passed it with high marks. My three years of typing and shorthand in high school finally paid off. I met many girls from all parts of the United States, but never became close with any of them. I was too shy.

During this schooling, I was anxious to know where I would be serving the remainder of my enlistment. Students could request duty anywhere in the US. If there was a vacancy they were sent there. I requested the West Coast.

Back to the West Coast

My first duty station was downtown Seattle where I was assigned to an aircraft control center. I climbed ladders to put colored pins on a huge wall map so the officers would know the exact location of ships and planes at sea. The radioman of each plane called our office at least every hour giving their exact location. The planes were on constant alert for possible enemy activity.

Next door to our office was the Russian Embassy. The lone officer on duty came into our office once or twice a week just to look around. He looked impressive in his white uniform. He never stayed long and never spoke to anyone. We used to think he was just lonesome. We never knew if he spoke English or if he gathered any information while strolling through our office. We felt very uncomfortable whenever he was around.

Less than a year later, I was transferred to Tongue Point Naval Air Station, Astoria, Oregon. By this time the war in the Pacific was going full force. As ships came into port in Astoria, the Navy communications manuals were brought to our office for updating. New coding was inserted, deletions and corrections were made, and old outdated books were replaced by new books. I clearly remember coding a great number of radio signals in manuals for the Battle of Iwo Jima and the possible invasion of the Aleutian Islands in Alaska. The significance of this coding was not realized until after the Battle of Iwo Jima. Up to this time I was nonchalantly performing my assigned duties, but it really hit me hard when I found out the importance of what I was doing. I also typed court martial papers for sailors who were not being good boys. No typing errors were allowed on those papers, and if I made a typing error, I had to start over.

Sailors and ensign officers from the communications sections of their ships were detailed to our office to help bring coding data up to date, while their ships were in port for repairs or supplies. The WAVES called these young ensigns 90-day-blunders. They were younger than us and had no experience. The men from these ships were awestruck that women were in the Navy doing work that was vital. Most of the men did not resent the WAVES, but they could not get used to the fact the Navy had women replacing men that were so badly needed at sea. We enjoyed the sailors company and had some good times in spite of the fact it was wartime.

Looking out the windows of our office, we saw shipload after shipload of lumber leaving the harbor bound for Russia when our own country was so badly in need of lumber for building homes.

It was common knowledge that unidentified submarines were lurking in the waters off the coast of Oregon. After a few days the submarines disappeared. It was said every inch of the United States shoreline was mapped and photographed by the Japanese.

My next duty station was in Portland, Oregon. Our office was a converted scow moored in the Willamette River. Conventional office space in downtown buildings was impossible to rent. Every time a small ship or barge went up or down the river near our scow, we could hear the water in the bilges sloshing to and fro. This time I worked with teletypes. We sent messages, mostly to shore stations along the coast and to Marine Headquarters in San Francisco.

The Marine Corps had their recruiting office within walking distance of our office. They used the Navy’s teletype to send messages to their main office in San Francisco. Their runners for this job came to our office every morning to deliver and receive any messages. One of those runners was Bob Lincoln.

I thoroughly enjoyed my 34 months in the Navy. Now whenever I think about those days, I realize this was a time of great transition in my life. I was away from home and on my own. I gained self esteem and confidence and found out what the working world was all about.

I made many friends. Two of them, Opal from Pennsylvania and Glee from Wisconsin remained friends and kept in contact for many years.

When the war finally ended, the GIs were welcomed home and they started a new life. We at home had done everything asked of us to help our men on the fighting front.

No comments:

Post a Comment